If you think traveling the Silk Road is like following Route 66 with thematic signposts and a connect-the-dots map, you would be thinking like we did when we flew to Central Asia a month ago. And like we were, you would be mistaken.

We brought two misconceptions about the Silk Road to the Stans with us.

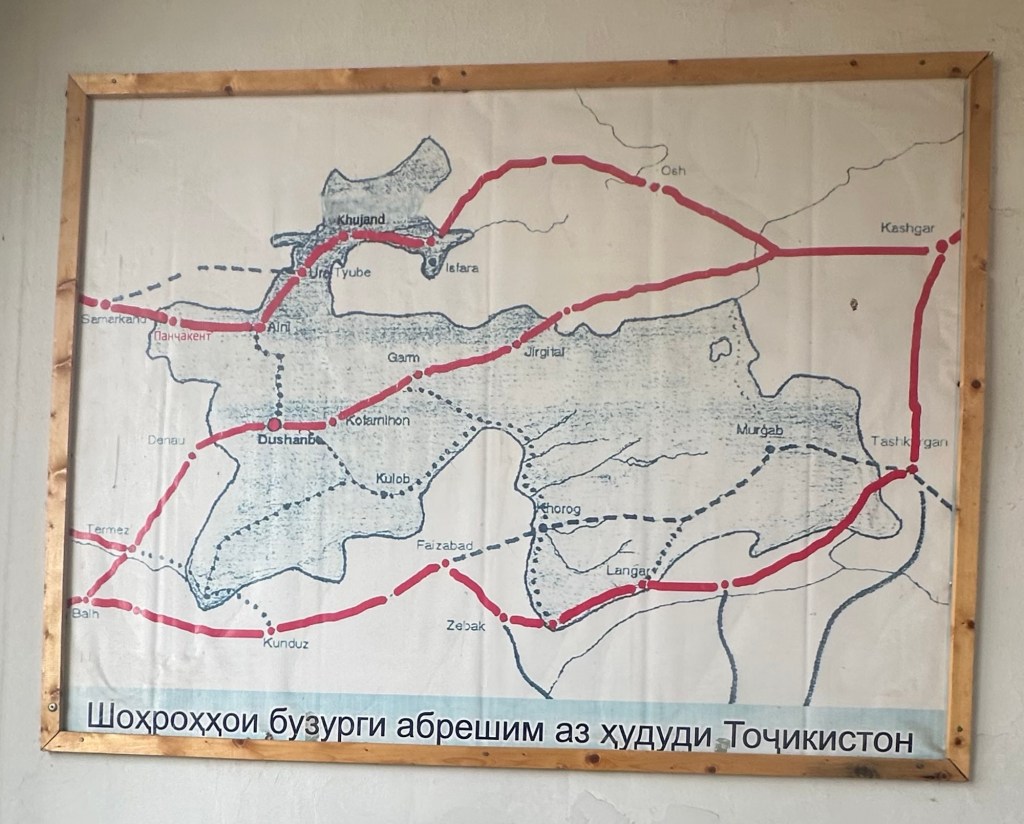

The first was that there is a literal “Silk Road” to see. In reality, “Silk Road” was a 19th-century academic term for the vast network of trade routes that criss-crossed Asia from China to the Mediterranean from the 2nd century BCE to the mid-15th century CE. More the US interstate system than Route 66.

Strategic centers developed where the routes crossed. Fabled settlements like Samarkand, Bukhara and Khiva were among these, and they bring us to our second misconception.

The early trading centers of the silk network were basically all wiped out when Genghis Khan and his gang came through in 1219-1221. Anything predating the invasion (i.e., most of the system’s history) is typically an archaeological site that survived only because it was already abandoned by the 13th century. Old Nissa outside Ashgabat, Turkmenistan, is one example.

The few (precious few) structures Genghis left standing were those of use to him, perhaps most famously the 12th-century Kalyan (Karon) Minaret of Bukhara. Legend has it Genghis was so besotted by the structure’s grandeur he ordered it saved. As the tallest building in the city, our guide said he actually spared it for its military value as a watchtower.

In Khiva, a dozen or so of the exquisite wooden pillars from the 10th-century Djuma (Juma) Mosque survive to be admired but only because they were intact enough to be repurposed after Genghis’s visit. The rest of the mosque dates from the 16th century.

Luckily for Silk Road seekers, some of the landscape Genghis cleared was reclaimed 150 years later by Timur the Lame (Tamerlane) whose architectural ambitious were second only to his territorial appetites. “If you have doubts about our grandeur, look at our edifices,” Tamur is said to have declared as he erected one dazzling monument to his power after another. These are the Silk Road landmarks that still shine.

(Fun fact: Tamerlane married a several-times-great-granddaughter of Genghis Khan to legitimatize power, making him a descendant in-law who rebuilt where the outlaw laid waste.)

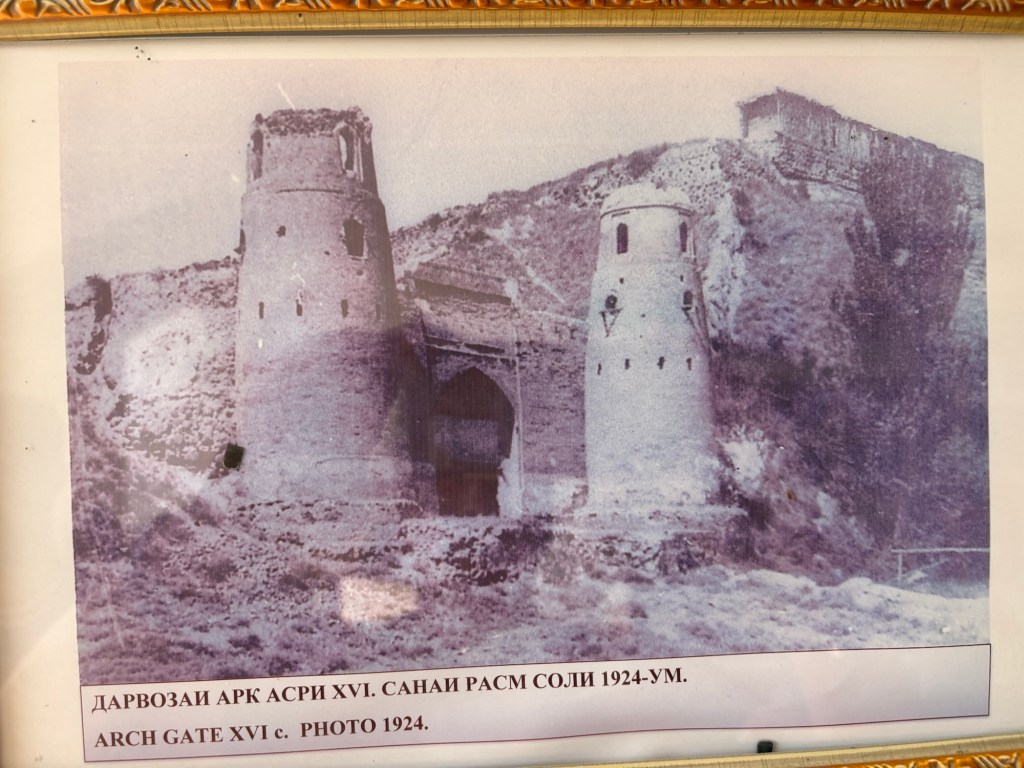

Like all empires, Tamerlane’s passed, too. Minor conquerors, earthquakes and the Soviets continued to take a toll on the old trade routes. The fortress Hisor in Tajikistan stood for more than a millennium, devastated by Genghis, resurrected by Tamerlane and still intact when the czar’s royal photographers came through in the 1890s.

Then came the Bolshevik Revolution, the people of Hisor had the temerity to resist the Soviets, and they responded by leveling everything but Hisor’s front gates. The structure was rebuilt from the old photos.

We came to Central Asia to illuminate a black hole in our knowledge and understand the Silk Road. No matter what may have surrendered to time and conquerors, the vast steppes, the intimidating deserts and the towering mountain ranges have not changed. As we crossed about one-third of a route caravans once plodded and walked through villages vibrant bazaars, the black hole shrank, and the Silk Road came back to life.

Your Questions Answered

Personamysteriously wrote: Did you get car sick? What was the driving too much seeing things ratio?

Until we reached the Turkmen border, the drive/see balance felt just right. We spent three weeks covering something like 1,500 miles mostly in cities or close enough to them for day trips on decent roads. In Turkmenistan, we traveled nearly 600 miles in less than 4 days, mostly on brutal roads. To give you an idea how brutal, our fitness watches count steps by the impact of a foot hitting the ground. On our driving days in Turkemistan, we racked up 15,000 “steps” a day even if we walked no farther than our yurt because that’s how many times we bounced. In retrospect, we wish we had flown into Ashgabat and done the rest with day trips.

As for car sickness, neither of us were bothered by it (including motion sickness-prone Doris), but we both experienced some disembarkation disorientation (that swaying sensation after leaving a boat) after long rock and roll rides.

I will miss your Partout journal entries. What a fabulous trip, and you both shared it elegantly through beautiful writing and photos.

Looking forward to seeing you soon,

Bob

>

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Bob, but don’t miss us yet! There are still a few we can’t resist posting.

LikeLike

Fabulous history lesson! Thank you so much.

LikeLike